Exploration Lab

(Sep – Dec 2023)

This zone presents six topics that invite you to explore maps with a scholar's mind. The families of European maps demonstrate how map research helps us understand mapmaking history, while the Menzies theory of the discovery of the Americas is an interesting case to test your ability to research and come to conclusions with the help of maps. The traveler stories lead you to reflect on the roles of maps and travelers in the history of cultural and knowledge exchange. You can also see maps that are open for speculation and further research. Lastly, you can find a late Qing map packed with cultural, historical, and geographical references, which lures you to dive in for lots of fun, be it fact or fiction.

Follow the exploration cards in each section to interact with the exhibits in ways that your curiosity leads you!

Nestorian Crosses

Courtesy of University Museum and Art Gallery, HKU

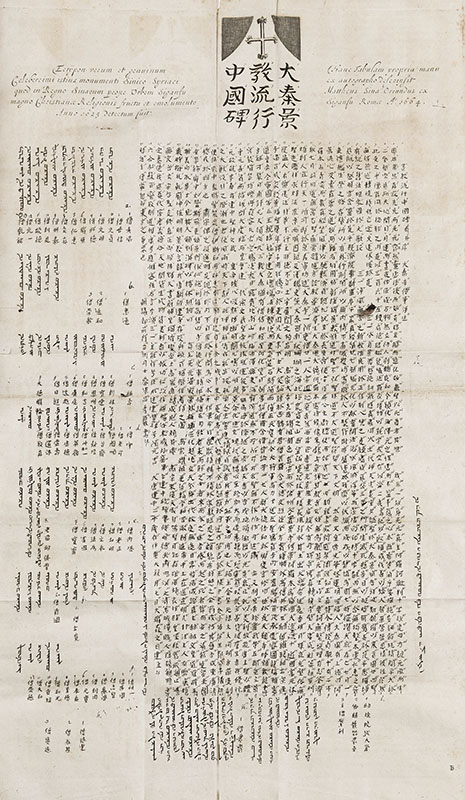

Nestorian Stele in Xi'an

HKUST Library DS708 .K585 1667

![<i>Gujin Diyu Quantu</i><br>[Complete Ancient and Modern Map]](../img/7.18.jpg)

Gujin Diyu Quantu

[Complete Ancient and Modern Map]

HKUST Library G7820 1895 .G8 1895

![<i>Chinae, olim sinarum regionis, nova descriptio</i><br>[China, formerly Region of China, A New Description]](../img/7.20.jpg)

Chinae, olim sinarum regionis, nova descriptio

[China, formerly Region of China, A New Description]

![<i>Imperii Sinarum nova descriptio</i><br>[A new description of the empire of China]](../img/7.32.jpg)

Imperii Sinarum nova descriptio

[A new description of the empire of China]

![<i>Carte la plus generale et qui comprend La Chine, la Tartarie Chinoise et le Thibet</i><br>[The most general map and which includes China, the Tartary Chinese, and Tibet]](../img/7.64.jpg)

Carte la plus generale et qui comprend La Chine, la Tartarie Chinoise et le Thibet

[The most general map and which includes China, the Tartary Chinese, and Tibet]

HKUST Library DS708 .D85 1737