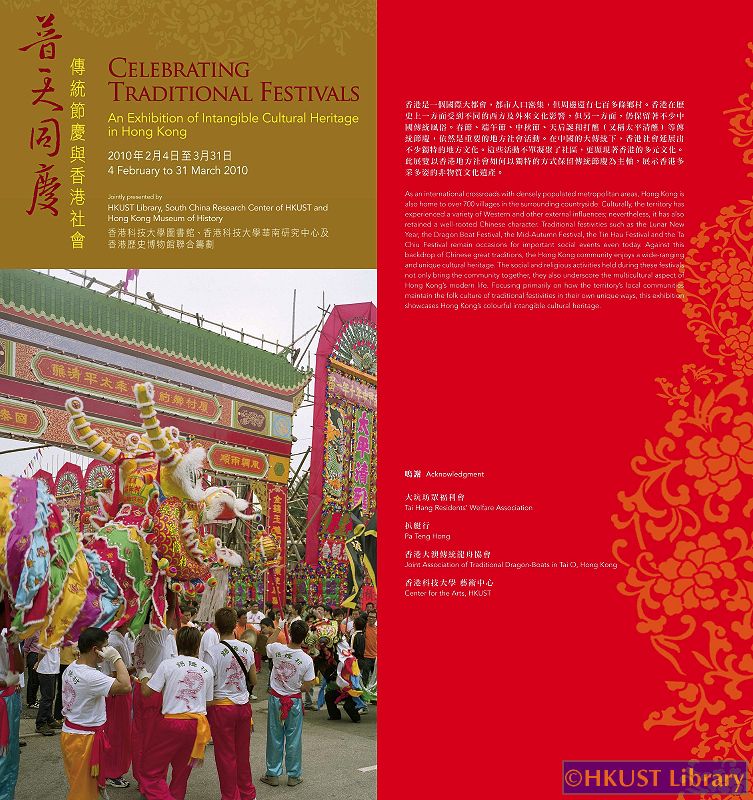

Foreword

As an international crossroads with densely populated metropolitan areas, Hong Kong is also home to over 700 villages in the surrounding countryside. Culturally, the territory has experienced a variety of Western and other external influences; nevertheless, it has also retained a well-rooted Chinese character. Traditional festivities such as the Lunar New Year, the Dragon Boat Festival, the Mid-Autumn Festival, the Tin Hau Festival and the Ta Chiu Festival remain occasions for important social events even today. Against this backdrop of Chinese great traditions, the Hong Kong community enjoys a wide-ranging and unique cultural heritage. The social and religious activities held during these festivals not only bring the community together, they also underscore the multicultural aspect of Hong Kong’s modern life. Focusing primarily on how the territory’s local communities maintain the folk culture of traditional festivities in their own unique ways, this exhibition showcases Hong Kong’s colourful intangible cultural heritage.

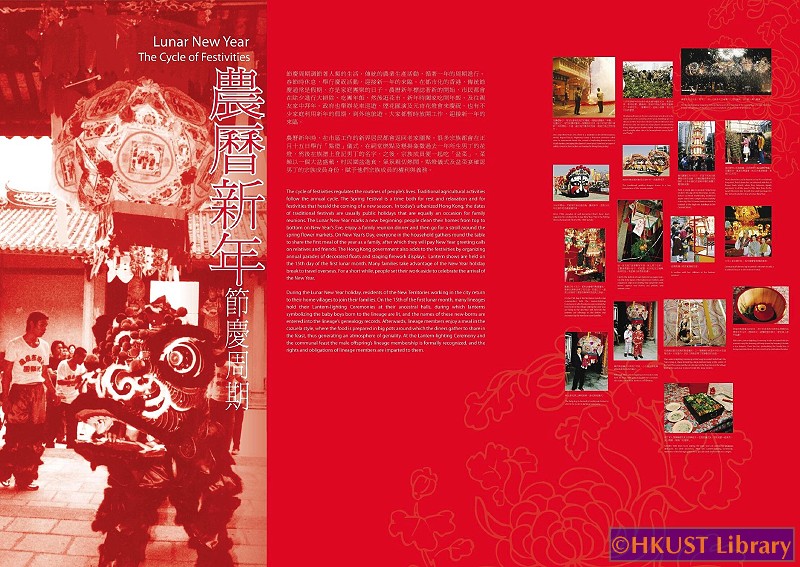

Lunar New Year

The cycle of festivities regulates the routines of people’s lives. Traditional agricultural activities follow the annual cycle. The Spring Festival is a time both for rest and relaxation and for festivities that herald the coming of a new season. In today’s urbanized Hong Kong, the dates of traditional festivals are usually public holidays that are equally an occasion for family reunions. The Lunar New Year marks a new beginning: people clean their homes from top to bottom on New Year’s Eve, enjoy a family reunion dinner and then go for a stroll around the spring flower markets. On New Year’s Day, everyone in the household gathers round the table to share the first meal of the year as a family, after which they will pay New Year greeting calls on relatives and friends. The Hong Kong government also adds to the festivities by organizing annual parades of decorated oats and staging rework displays. Lantern shows are held on the 15th day of the first lunar month. Many families take advantage of the New Year holiday break to travel overseas. For a short while, people set their work aside to celebrate the arrival of the New Year.

During the Lunar New Year holiday, residents of the New Territories working in the city return to their home villages to join their families. On the 15th of the first lunar month, many lineages hold their Lantern-lighting Ceremonies at their ancestral halls, during which lanterns symbolizing the baby boys born to the lineage are lit, and the names of these new-born are entered into the lineage’s genealogy records. Afterwards, lineage members enjoy a meal in the cazuela style, where the food is prepared in big pots around which the diners gather to share in the feast, thus generating an atmosphere of geniality. At the Lantern-lighting Ceremony and the communal feast the male o spring’s lineage membership is formally recognized, and the rights and obligations of lineage members are imparted to them.

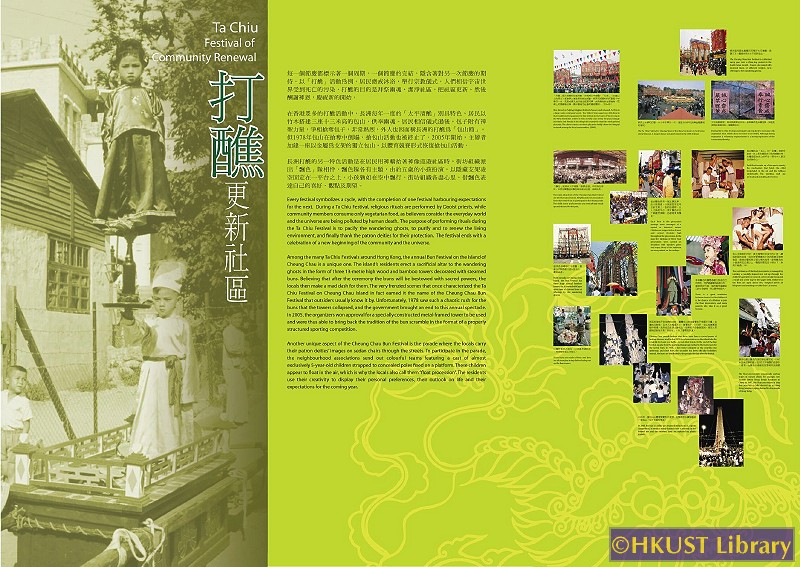

Ta Chiu

Every festival symbolizes a cycle, with the completion of one festival harboring expectations for the next. During a Ta Chiu Festival, religious rituals are performed by Daoist priests, while community members consume only vegetarian food, as believers consider the everyday world and the universe are being polluted by human death. The purpose of performing rituals during the Ta Chiu Festival is to pacify the wandering ghosts, to purify and to renew the living environment, and finally thank the patron deities for their protection. The festival ends with a celebration of a new beginning of the community and the universe.

Among the many Ta Chiu Festivals around Hong Kong, the annual Bun Festival on the island of Cheung Chau is a unique one. The island’s residents erect a sacrificial altar to the wandering ghosts in the form of three 13-metre high wood and bamboo towers decorated with steamed buns. Believing that after the ceremony the buns will be bestowed with sacred powers, the locals then make a mad dash for them. The very frenzied scenes that once characterized the Ta Chiu Festival on Cheung Chau Island in fact earned it the name of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival that outsiders usually know it by. Unfortunately, 1978 saw such a chaotic rush for the buns that the towers collapsed, and the government brought an end to this annual spectacle. In 2005, the organizers won approval for a specially constructed metal-framed tower to be used and were thus able to bring back the tradition of the bun scramble in the format of a properly structured sporting competition.

Another unique aspect of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival is the parade where the locals carry their patron deities’ images on sedan chairs through the streets. To participate in the parade, the neighborhood associations send out colorful teams featuring a cast of almost exclusively 5-year-old children strapped to concealed poles fixed on a platform. These children appear to float in the air, which is why the locals also call them “ oat procession”. The residents use their creativity to display their personal preferences, their outlook on life and their expectations for the coming year.

Tin Hau Festival

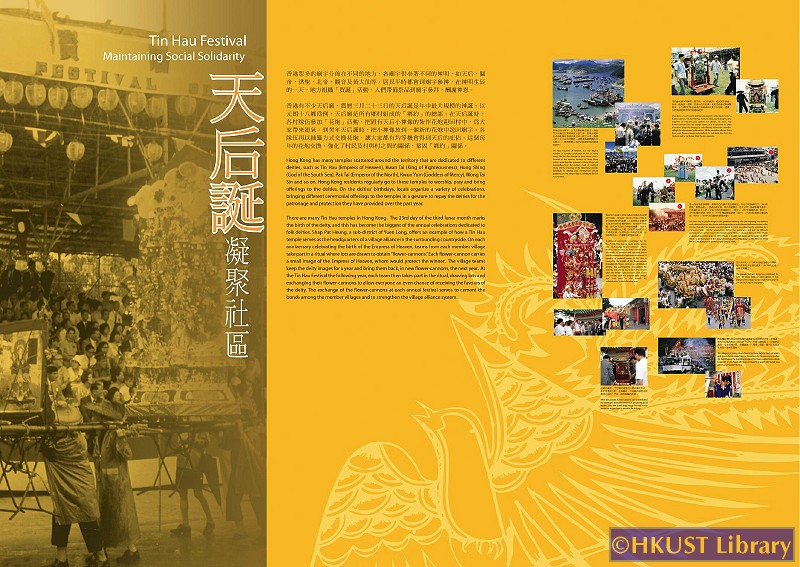

Hong Kong has many temples scattered around the territory that are dedicated to different deities, such as Tin Hau (Empress of Heaven), Kwan Tai (King of Righteousness), Hung Shing (God of the South Sea), Pak Tai (Emperor of the North), Kwun Yum (Goddess of Mercy), Wong Tai Sin and so on. Hong Kong residents regularly go to these temples to worship, pray and bring offerings to the deities. On the deities’ birthdays, locals organize a variety of celebrations, bringing different ceremonial offerings to the temples in a gesture to repay the deities for the patronage and protection they have provided over the past year.

There are many Tin Hau temples in Hong Kong. The 23rd day of the third lunar month marks the birth of the deity, and this has become the biggest of the annual celebrations dedicated to folk deities. Shap Pat Heung, a sub-district of Yuen Long, offers an example of how a Tin Hau temple serves as the headquarters of a village alliance in the surrounding countryside. On each anniversary celebrating the birth of the Empress of Heaven, teams from each member village take part in a ritual where lots are drawn to obtain “flower-cannons.” Each flower-cannon carries a small image of the Empress of Heaven, whom would protect the winner. The village teams keep the deity images for a year and bring them back, in new flower-cannons, the next year. At the Tin Hau Festival the following year, each team then takes part in the ritual, drawing lots and exchanging their flower-cannons to allow everyone an even chance of receiving the favors of the deity. The exchange of the flower-cannons at each annual festival serves to cement the bonds among the member villages and to strengthen the village alliance system.

Dragon Boat Festival

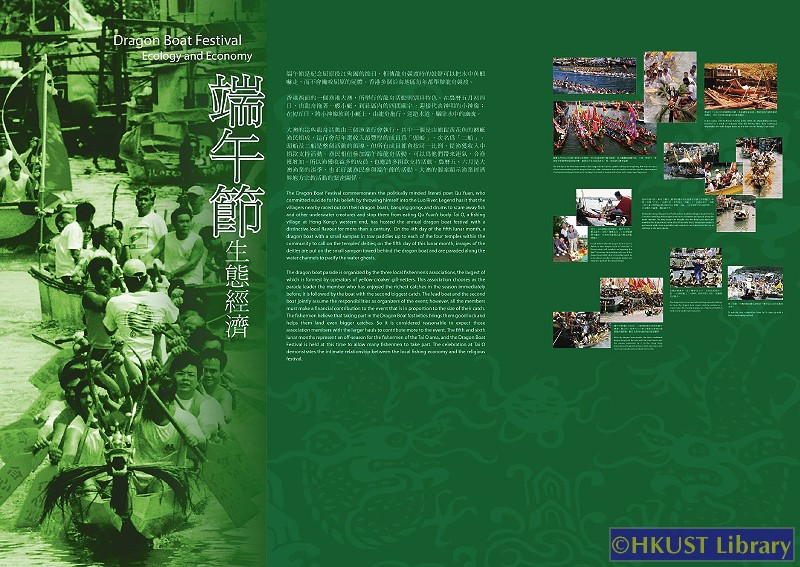

The Dragon Boat Festival commemorates the politically minded literati poet Qu Yuan, who committed suicide for his beliefs by throwing himself into the Luo River. Legend has it that the villagers nearby raced out on their dragon boats, banging gongs and drums to scare away fish and other underwater creatures and stop them from eating Qu Yuan’s body. Tai O, a shing village at Hong Kong’s western end, has hosted the annual dragon boat festival with a distinctive local flavour for more than a century. On the 4th day of the fifth lunar month, a dragon boat with a small sampan in tow paddles up to each of the four temples within the community to call on the temples’ deities; on the fifth day of this lunar month, images of the deities are put on the small sampan towed behind the dragon boat and are paraded along the water channels to pacify the water ghosts.

The dragon boat parade is organized by the three local fishermen’s associations, the largest of which is formed by operators of yellow-croaker gill-netters. This association chooses as the parade leader the member who has enjoyed the richest catches in the season immediately before; it is followed by the boat with the second biggest catch. The lead boat and the second boat jointly assume the responsibilities as organizers of the event; however, all the members must make a financial contribution to the event that is in proportion to the size of their catch. The fishermen believe that taking part in the Dragon Boat festivities brings them good luck and helps them land even bigger catches. So it is considered reasonable to expect those association members with the larger hauls to contribute more to the event. The fifth and sixth lunar months represent an o -season for the fishermen of the Tai O area, and the Dragon Boat Festival is held at this time to allow many fishermen to take part. The celebration at Tai O demonstrates the intimate relationship between the local shing economy and the religious festival.

Mid-Autumn Festival

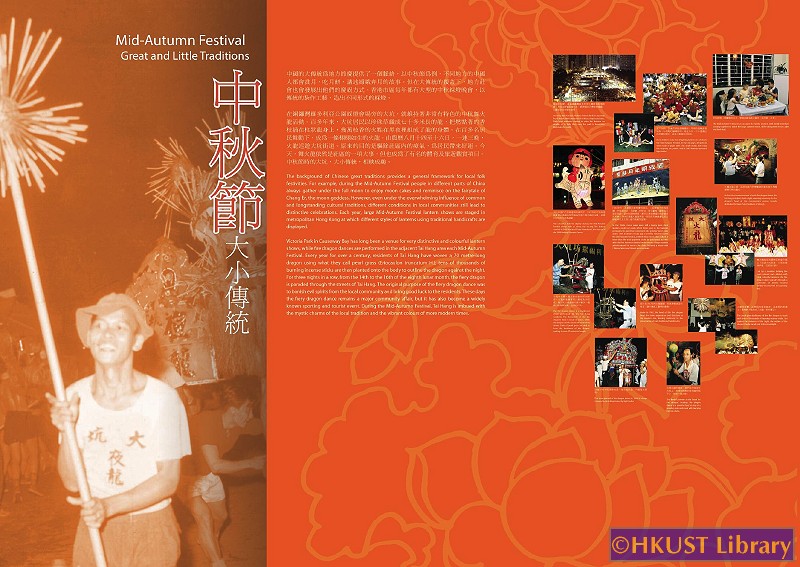

The background of Chinese great traditions provides a general framework for local folk festivities. For example, during the Mid-Autumn Festival people in different parts of China always gather under the full moon to enjoy moon cakes and reminisce on the fairytale of Chang Er, the moon goddess. However, even under the overwhelming influence of common and longstanding cultural traditions, different conditions in local communities still lead to distinctive celebrations. Each year, large Mid-Autumn Festival lantern shows are staged in metropolitan Hong Kong at which different styles of lanterns using traditional handicrafts are displayed.

Victoria Park in Causeway Bay has long been a venue for very distinctive and colorful lantern shows, while re dragon dances are performed in the adjacent Tai Hang area each Mid-Autumn Festival. Every year for over a century, residents of Tai Hang have woven a 70 meter-long dragon using what they call pearl grass (Eriocaulon truncatum H.); tens of thousands of burning incense sticks are then planted onto the body to outline the dragon against the night. For three nights in a row, from the 14th to the 16th of the eighth lunar month, the fiery dragon is paraded through the streets of Tai Hang. The original purpose of the fiery dragon dance was to banish evil spirits from the local community and bring good luck to the residents. These days the fiery dragon dance remains a major community affair, but it has also become a widely known sporting and tourist event. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, Tai Hang is imbued with the mystic charms of the local tradition and the vibrant colors of more modern times.

Cantonese Opera

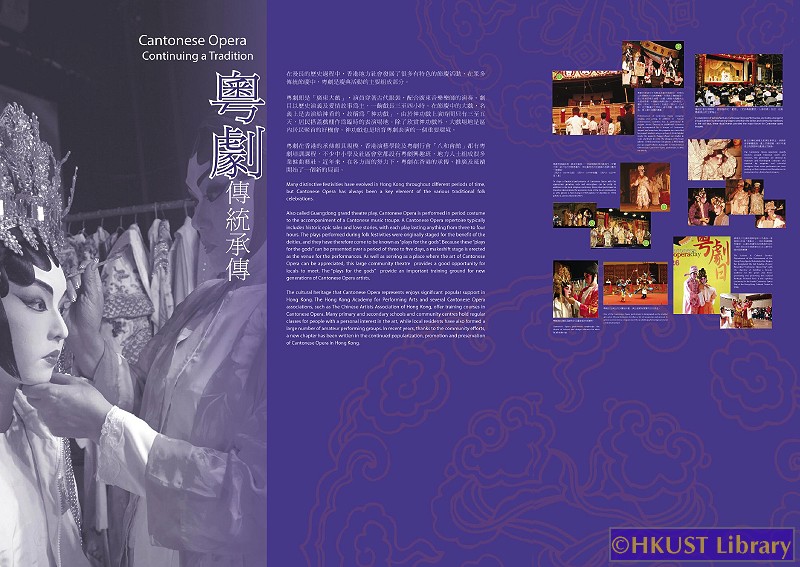

Many distinctive festivities have evolved in Hong Kong throughout different periods of time, but Cantonese Opera has always been a key element of the various traditional folk celebrations.

Also called Guangdong grand theatre play, Cantonese Opera is performed in period costume to the accompaniment of a Cantonese music troupe. A Cantonese Opera repertoire typically includes historic epic tales and love stories, with each play lasting anything from three to four hours. The plays performed during folk festivities were originally staged for the benefit of the deities, and they have therefore come to be known as “plays for the gods”. Because these “plays for the gods” can be presented over a period of three to five days, a makeshift stage is erected as the venue for the performances. As well as serving as a place where the art of Cantonese Opera can be appreciated, this large community theatre provides a good opportunity for locals to meet. The “plays for the gods” provide an important training ground for new generations of Cantonese Opera artists.

The cultural heritage that Cantonese Opera represents enjoys significant popular support in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts and several Cantonese Opera associations, such as The Chinese Artists Association of Hong Kong, offer training courses in Cantonese Opera. Many primary and secondary schools and community centers hold regular classes for people with a personal interest in the art, while local residents have also formed a large number of amateur performing groups. In recent years, thanks to the community efforts, a new chapter has been written in the continued popularization, promotion and preservation of Cantonese Opera in Hong Kong.

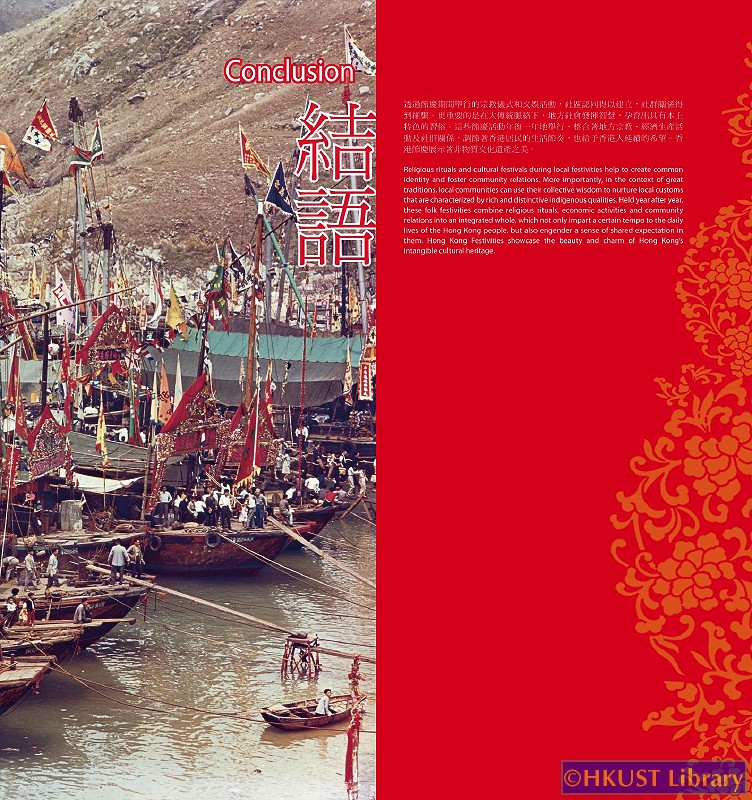

Conclusion

Religious rituals and cultural festivals during local festivities help to create common identity and foster community relations. More importantly, in the context of great traditions, local communities can use their collective wisdom to nurture local customs that are characterized by rich and distinctive indigenous qualities. Held year after year, these folk festivities combine religious rituals, economic activities and community relations into an integrated whole, which not only impart a certain tempo to the daily lives of the Hong Kong people, but also engender a sense of shared expectation in them. Hong Kong Festivities showcase the beauty and charm of Hong Kong’s intangible cultural heritage.

Ping Yuan and Kinmay W Tang Gallery