Foreword

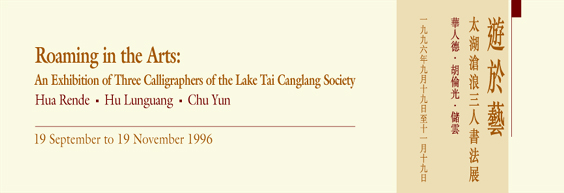

In the Chinese cultural tradition there is no art form more representative, long-lasting and broadly appreciated than calligraphy. In 1991, the Library at HKUST inaugurated its gallery space with an exhibtion of the modern-style calligraphy of Huang Miaozi. Since then there have been exhibitions of rubbings, paintings, ancient maps and contemporary painting, but this is the first time in our five year history that we have held an exhibition of classical style calligraphy together with seal carving.

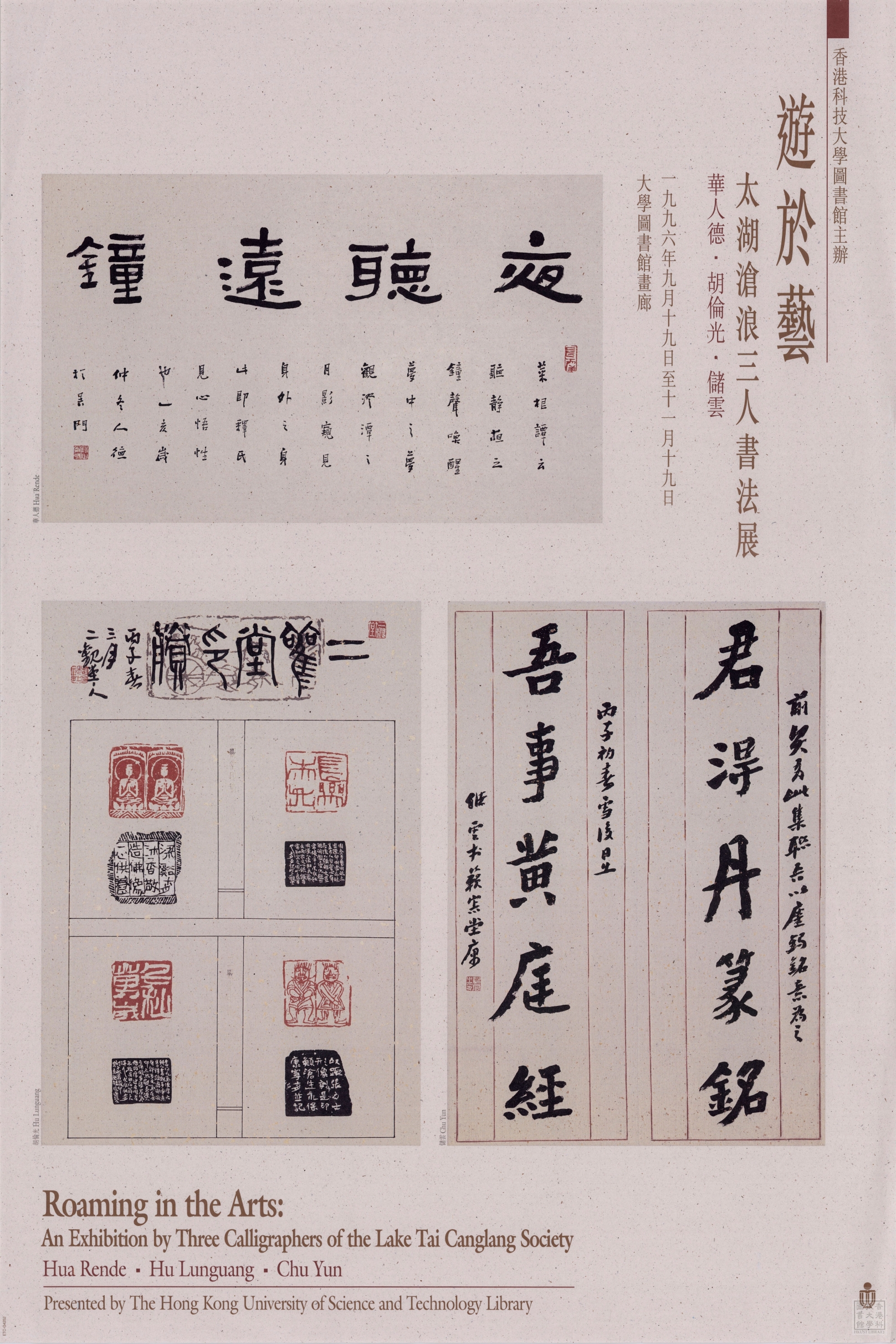

In the spring of 1995, Mr. Hua Rende came to Hong Kong and visited our library in conjunction with his professional work as librarian of rare books at Suzhou University. We became acquainted and I learned that Mr. Hua was the founder of the Canglang Calligraphy Society. Correspondence followed, and eventually a plan for this current exhibition of three calligraphers from the Canglang Society took form. Confucius said: “Set heart on the Way, base yourself on virtue, lean upon benevolence and roam in the arts.” This is the inspiration for the title of this exhibition, “Roaming in the Arts.”

I would like to express my special gratitude to Dr. Hui-shu Lee for first introducing Mr. Hua Rende to me and later writing an excellent introduction for this exhibition.

Min-min Chang

University Librarian

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Encountering Brush and Ink: Notes on Three Calligraphers of the Canglang Society

Calligraphy has a long and continuous history of over three thousand years in China. From ideographic signs which functioned as characters for writing there gradually evolved established scripts, strokes, set character compositions and consciousness of writing’s aesthetic qualities until, ultimately, calligraphy in China became a pure art capable of expressing an artist’s creativity. Over this long period of time, not only did such different forms of writing emerge as the seal, clerical, cursive, semi-cursive and standard scripts, but also a rich assortment of personal styles as well as elaborate attempts to explain calligraphy’s secrets in theory and method. In China, calligraphy joins painting to form the “twin jewels” of the visual arts. Outside of China it stands as one of the great fine arts of the world ¯ a fitting symbol of the splendors of Chinese culture.

Chinese calligraphy’s emergence as a fine art capable of realizing profound depths of personal expressiveness is closely tied to both the unique qualities of Chinese characters and the writing brush. A Chinese character combines shape, design, sound and meaning in one individual graph, so that nature’s forms and ideas are reduced and abbreviated into a few simple brush strokes. Each individual character becomes a complete picture of its own. As for the brush, though simple in appearance, this writing tool possesses tremendous flexibility: sharpness, smoothness, roundness and strength are among its characteristics. Properly handled, the brush imparts a three-dimensional quality to the characters. Its movements are limitless, its sensitivity to the writer’s actions spontaneous, and for this reason the brush taps the very source of the calligrapher’s creative powers. Once the basic rules and methods are mastered, the brush moves with the freedom of a celestial horse galloping across the sky. The interaction of strokes and dots, subtleties of composition and such qualities of brush handling as lifting, pressing, pausing, stuttering and speed all present to the viewer a sense of power and beauty in a limitless world of imaginary space. Those who are able to read the characters can share in the subtle meanings. Those who do not can still follow the movements of dots and strokes and sense the circular energies that traverse the columns of writing, thus losing themselves in the pure delight of abstract beauty. The degree of experience one may bring to the viewing of calligraphy may vary, but there is no difference of quality in our enjoyment.

In traditional China, the practice and transmission of calligraphy was closely tied to the practical necessity of becoming literate and the exams that led to an official career. For this reason, the art of calligraphy became something broadly shared and appreciated in Chinese society. In twentieth century China, however, with the rising importance of the sciences and the pursuit of modernity, the traditional Chinese brush gradually became replaced by pen and pencil, so that now it is common to hear the lament that few truly appreciate and understand this art. Yet, because the art of calligraphy has its roots in the written language, it is also true that calligraphy has deeply entwined itself into the everyday experiences of the common person. From the simple notes we write to one another to commercial shop signs and advertising to the titles and encomia on tablets and gateways at famous sites ¯ when written well all such things awaken the aesthetic sensibilities of the Chinese so that they linger with pleasure, savoring the beauty and force of the writing. In fact, the attraction of Chinese calligraphy is not limited to China alone. For centuries this art has been followed and practiced in Korea and Japan, and it is said to have played an inspiring role for the Abstract Expressionist painters of the West. Even those who do not read Chinese have found themselves captivated by calligraphy’s abstract beauty and rhythmic movements. From this we know that Chinese calligraphy transcends time and space and possesses a certain modern sensibility.

Earlier in this century there were a number of excellent writers who continued calligraphy’s transmission as a fine art, including Wu Changshi (1844-1927) and Shen Meisou (1850-1922). After mid-century, however, the practice of calligraphy had weakened noticeably. It is only in recent times that calligraphy has again been reinvigorated, and this, in no small measure, is due to the efforts of Hua Rende of Suzhou. In 1987, Hua Rende organized some of the best young and middle-aged amateur calligraphers and seal carvers of China to form the Canglang Calligraphy Society. The members of the Canglang Society come from various professions, many of which have little if anything to do with the arts of calligraphy and painting. These are all modest individuals ¯ private scholars bound by a common love for calligraphy. Every year they gather at some historical site in China in order to share their gains and discoveries in research and art with one another, paying their lodging costs by writing calligraphy and carving seals for the proprietors. It has been common practice for all of the individuals in the society to donate their art so that the proceeds from a sale can help in the publication of a group or individual catalogue. These actions, reminiscent of the generosity and devotion of traditional society, deserve our deep respect. In recent years members of the Canglang Calligraphy Society have had a number of exhibitions, both in China and abroad. Their work has attracted much attention and praise, to the degree that many consider the group’s art to be the best among relatively young calligraphers today, and an emerging pillar upon which the future of Chinese calligraphy will be built.

This exhibition of three members’ work came about as a result of a fortuitous visit to the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology by Hua Rende, the founder of the Canglang Society. The three participants all live in relative proximity to one another in the general region of Lake Taihu in Jiangsu Province: Hua Rende hails from Suzhou, Hu Lunguang from Wuxi and Chu Yun from Yixing. Hua Rende is recognized and admired as a solid scholar as well as calligrapher. He is a graduate of Beijing University and currently works as the librarian of Chinese rare books at Suzhou University. In addition to his talents as a calligrapher, Hua Rende is an outstanding historian and an excellent writer. His calligraphy follows the archaic styles of writing known from stelae inscriptions and letters of pre-Tang dynasty date. He excels in all of the scripts, but his clerical script writing is particularly noteworthy, combining brushwork that is strong yet calm in appearance with tightly compact character compositions. Hua Rende is blessed with a mild, gentlemanly disposition, and he possesses a keen interest in Buddhism (his style name is Weimo, after the famous Indian Buddhist layman Vimalakirti). Earlier in his development as a calligrapher he modeled himself after the talented Buddhist monk and calligrapher Master Hongyi (1880-1942), whom Hua Rende admired tremendously. For all of these reasons, Hua Rende’s calligraphy bears an air of quiet detachment. It is a relaxed yet profound style of writing, just like the person, and bears witness to the old adage in China that calligraphy is a picture of the writer’s heart.

Hu Lunguang always signs his work with the sobriquet Master of the Double View Hall. This is borrowed from Liu Xizai’s book Shu gai (Outline of Calligraphy), in which it is said that calligraphy has two views: the view of objects and the view of oneself. Coincidentally, there are also two equally splendid accomplishments to Hu Lunguang’s art to be viewed ¯ calligraphy and seal carving. Hu Lunguang’s calligraphy is rooted in a deep study of the archaic seal scripts known from bronze vessels of the ancient periods as well as calligraphy found in Six Dynasties Period stelae and devotional inscriptions for the making of Buddhist images. He, too, is skilled in all scripts, and has successfully evolved his own personal style of writing. Hu Lunguang wields the brush with slow, deliberate movements to form densely constructed characters whose assemblage of interacting strokes present a slightly unusual flavor. Hu Lunguang’s seal carving also stems from a careful study of ancient precedents. He bases his style on the seals of the Zhou, Qin and Han dynasties, supplementing this with a keen awareness of more recent interpretations from later periods. His study of the early scripts, ancient roof tiles, grave inscriptions and devotional inscriptions have also long exposed Hu Lunguang to the images that commonly accompany such writing. For this reason, he is often inspired to playfully carve both religious and folk images on the sides of seals as well as on bricks. These images are composed of lines of a decidedly antique flavor. Strong and tense, the impression is one of timeless endurance. One other characteristic of Hu Lunguang’s work should be mentioned. He often combines his seal and brick carving together with his calligraphy to make a new kind of pictorial ensemble. Integrated in form and content, his work is at once brimming with a sense of antiquity while presenting an entirely modern form of inscribed devotional image.

Chu Yun’s calligraphy also looks back to the Six Dynasties Period and earlier for inspiration. He is primarily influenced by writing known from Northern Wei Period and Han dynasty stelae. Chu Yun is particularly interested in the draft-cursive script (zhangcao), which he has studied from archaeologically discovered scraps of writing on paper and bamboo strips from the western regions of China. These serve as the basis for his own highly personal style of writing ¯ a mixture of cursive and semi-cursive which is characterized by a kind of stuttering brushwork that is weighty yet uninhibited. Chu Yun studies the writing of the ancient dynasties, Shang and Zhou, which he often assembles into matching couplets. He paints landscapes, following the manner of the great master Huang Binhong (1865-1955), which, like his calligraphy, are infused with the hoary, substantial qualities of antiquity. Moreover, because he lives in Yixing, home of the distinctive purple-clay ceramic used for tea ware, Chu Yun often displays his talents by carving calligraphy and pictures on teapots. The Chinese have a saying, “the world within a pot,” and one could say that Chu Yun’s inspired work with the Yixing teaware continues this idea of the paradise world in miniature.

These three calligraphers all have their individual styles and strengths, but they also have certain points in common. The most important is an approach that looks back to the “metal and stone” (jinshi) school of calligraphy that was dominant in the late Qing dynasty and early Republican period. The metal and stone school sought to go directly back to the original writings of earlier times as they were discovered on ancient bronze vessels (metal) and old stelae (stone). Hua Rende, Hu Lunguang and Chu Yun basically ignore the well-trodden path set down by the famous calligraphers of the Tang and later dynasties and push back to the origins of early writing ¯ an attempt to dig out the secrets of the ancients. They thus gain most of their inspiration from ancient bronze inscriptions, stelae and other sources of early writing. Moreover, the three calligraphers approach this early calligraphy with a genuine seriousness of purpose. They are not content simply to copy the outer forms of their models, stroke by stroke, but rather seek to gain the essence of the writing, whether in brush movement, composition or abstract force. To this they combine their own habits of brushwork, pursuing the natural qualities of plainness and (seeming) awkwardness that is associated with early writing. In this way, the three calligraphers are able to assimilate and transform their models into their own personal styles of writing. Looking at their calligraphy and seal carving, our feelings for antiquity are aroused ¯ we follow them on their inspired journeys through history to the brilliance of early writing. At the same time, each work is itself a special individual effort that provides immeasurable viewing pleasure. These ensembles of pictures and writing possess a sense of the modern ¯ a visual feast for all.

These three calligraphers all have their individual styles and strengths, but they also have certain points in common. The most important is an approach that looks back to the “metal and stone” (jinshi) school of calligraphy that was dominant in the late Qing dynasty and early Republican period. The metal and stone school sought to go directly back to the original writings of earlier times as they were discovered on ancient bronze vessels (metal) and old stelae (stone). Hua Rende, Hu Lunguang and Chu Yun basically ignore the well-trodden path set down by the famous calligraphers of the Tang and later dynasties and push back to the origins of early writing ¯ an attempt to dig out the secrets of the ancients. They thus gain most of their inspiration from ancient bronze inscriptions, stelae and other sources of early writing. Moreover, the three calligraphers approach this early calligraphy with a genuine seriousness of purpose. They are not content simply to copy the outer forms of their models, stroke by stroke, but rather seek to gain the essence of the writing, whether in brush movement, composition or abstract force. To this they combine their own habits of brushwork, pursuing the natural qualities of plainness and (seeming) awkwardness that is associated with early writing. In this way, the three calligraphers are able to assimilate and transform their models into their own personal styles of writing. Looking at their calligraphy and seal carving, our feelings for antiquity are aroused – we follow them on their inspired journeys through history to the brilliance of early writing. At the same time, each work is itself a special individual effort that provides immeasurable viewing pleasure. These ensembles of pictures and writing possess a sense of the modern – a visual feast for all.

Hui-shu Lee

Introduction of Three Calligraphers of the Canglang Society

The Canglang Calligraphy Society, established on December 20, 1987 by the side of Canglang Pavilion, Suzhou, is a non-governmental organization transcending regional boundaries and embracing both young and middle-aged amateur calligraphers. It aims at preserving the art of Chinese calligraphy and seal carving, strengthening their lateral connections, and initiating high-quality research as well as academic exchange in an effort to boost Chinese culture.With this in mind, the Society has staged exhibitions of its members’ works and of Chinese calligraphy and seal carving at the National Art Centre, Taiwan, the Gallery of the Institute of Art, Rutgers University, USA, and the Alexandria Library Gallery, USA. In addition, the Society helped organize the Exhibition of Chinese Seal Carving hosted by Yale University, USA, and provided part of the exhibit; it has also held in Changzhou, Jiangsu, an international symposium on the history of Chinese calligraphy.Hua Rende, Hu Lunguang and Chu Yun, all members of the Society, live respectively in Suzhou, Wuxi, and Yixing, cities by the side of Lake Taihu. In their spare time, they often gather and learn from each other in the hope of refining their minds and improving their art. An ancient Chinese song says: “When the water is clear, it washes the strings of my cap; when the water is muddy, it washes my feet.” There is also an old saying in China: ” If one does not stimulate one’s art, one is unable to enjoy learning. Preserve it, nourish it, absorb it and then roam in it.” This exhibition is therefore entitled “Roaming in the Arts”.

Hua Rende, also named Weimo, was born in March 1947. A native of Wuxi, Jiangsu, he graduated in 1982 from the University of Beijing with a BA degree in Library Science. He is currently Head of the Special Reference Collection and Research Associate of the Suzhou University Library, member of the Society of Library Science of China, academic member of the Association of Chinese Calligraphers, and Chief Executive of the Canglang Calligraphy Society.

| 1981 | Won the third prize with a scroll displaying the running-style calligraphy in the first National Exhibition of University Students’ Calligraphy held in Beijing |

| 1983 | Participated in the first National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers held in Beijing, and an Exhibition of Couplets Written in the Clerical Style held in Nanchang |

| 1986 | Participated in the second National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers held in Beijing, and won a National Award for Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers with a couplet written in the clerical style calligraphy, he being listed above the other nine winners |

| 1987 | Couplets written in the clerical style displayed in the third National Exhibition of Calligraphy and Seal Carving held in Zhengzhou |

| 1988 | Works displaying on square paper the running-style calligraphy exhibited upon special invitation in the third National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers held in Hefei |

| 1989 | Couplets written in the running style won a third-class prize in the fourth National Exhibition of Calligraphy and Seal Carving held in Beijing |

| 1990 | Couplets written in the running style displayed in the first International Exhibition for the Interflow of Calligraphic Art held in Singapore |

| 1993 | Served on the Selection Panel for the fifth National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers held in Beijing, but sent in no works for exhibition |

| 1993 | Couplets written in the running style displayed in the second International Exhibition for the Interflow of Calligraphic Art held in Beijing |

| 1995 | Served on the Selection Panel for the sixth National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers held in Beijing, and couplets written in the running style exhibited upon special invitation |

| 1995 | Couplets written in the clerical style displayed in the third International Exhibition for the Interflow of Calligraphic Art held in Tokyo, Japan |

Hua Rende has also served on the Theses Selection Panel for the fourth International Symposium on Calligraphy, and is Deputy Secretary-General of the National Selection Panel for Calligraphic Scholarship Awards. Dozens of his theses and other works on calligraphy have been presented or published.

Hu Lunguang, who styled himself Erguantang Master, was born in January 1951. A native of Wuxi, Jiangsu, he started his calligraphic studies by following the footsteps of the Tang masters. Later, under the instruction of Zhang Zhengyu, Zhu Qizhan, Guan Liang, and Gao Shinong, he switched to the study of inscriptional writings on the stone tablets of the Northern Dynasty, and on the sacrificial vessels of the Three Dynasties.As for seal carving, he based his art chiefly on the emperors’ and kings’ seals of the Zhou and Qin dynasties, and also the seals of the Han dynasty, though he learned from other sources as well.

Hu graduated in 1991 from the Institute of Design, the Wuxi University of Light Industry, his specialization being indoor appliances design. In 1994, he was appointed Chief Supervisor of Art in the Donglin Art Development Company, Wuxi, and is currently a member of the Association of Chinese Calligraphers and of the Canglang Calligraphy Society.

| 1983 | Participated in the National Invitation Exhibition of the Works of Some Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers |

| 1984 | Participated in the first National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers and Seal Carvers |

| 1986 | Participated in the fourth Seal Carving Exhibition of Japan |

| 1988 | Exhibition in Taiwan |

| 1988 | Exhibition in Macao |

| 1988 | Participated in the first National Exhibition of Seal Carving |

| 1989 | Participated in the first International Exhibition of the Works of Young Calligraphers |

| 1989 | Participated in the fourth National Exhibition of Calligraphy and Seal Carving |

| 1990 | Exhibition in the Gallery of the Institute of Art, Rutgers University, USA |

| 1990 | Exhibition in the Center of Chinese Culture, San Francisco, USA |

| 1992 | Works exhibited in and collected by the Institute of Art, Yale University, USA |

Articles on Hu have been published in Chinese Calligraphy, Taiwan’s Calligraphy Education, and USA’s World Weekly. An article on the artist has also been presented at a symposium organized by the Sino-US Association in New York.

Chu Yun, born in April 1948, is a native of Yixing, Jiangsu. When still a child, he had a penchant for painting and calligraphy. In 1966, he learned landscape painting under the instruction of Mr Jing Weichen, a local artist. In 1970, he went to northwest China and engaged himself in creative painting. In 1983, he went to study in the Department of Art of the Normal University of Nanjing. Appointed Vice Chairman of the Yixing Literary Association in 1985, he is now a member of the Association of Chinese Calligraphers and the Canglang Calligraphy Society, as well as a senior art instructor.

| 1985 | Participated in an international calligraphy exhibition held in Zhengzhou |

| 1987 | Participated in the third National Exhibition of Calligraphy |

| 1989 | Participated in the fourth National Exhibition of Calligraphy, and won a National Award |

| 1990 | Participated in the third International Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers, and won an Artistic Excellence Award Participated in the first International Exhibition for the Interflow of Calligraphic Art held in Singapore |

| 1992 | Participated in the fourth National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers Participated in an Exhibition of the Works of Famous Chinese and Japanese Calligraphers held in Tokyo Participated in a Friendship Exhibition of Chinese and Japanese Calligraphy |

| 1993 | Participated in an Exhibition of Selected Works by Contemporary Chinese Artists and Calligraphers Participated in the second International Exhibition for the Interflow of Calligraphic Art |

| 1994 | Participated in the National Exhibition of Prize-Winning Calligraphic Works Won a silver medal in the first National Exhibition of Pillar-Scroll Calligraphy Participated in an Exhibition of the Selected Works of One Hundred Calligraphers of Contemporary China |

| 1995 | Participated in the sixth Friendship Exhibition of Prose and Poetry Reading by Chinese and Japanese Artists Participated in the 1995 International Calligraphic Art Exhibition held in Korea Participated in the sixth National Exhibition of the Art of Young and Middle-Aged Calligraphers Participated in the sixth National Exhibition of Calligraphy |

| 1996 | Participated in an Invitation Exhibition of Twenty Calligraphers of Contemporary China |

Chinese Calligraphy, A Kaleidoscope of Calligraphy, Taiwan’s Heaven and Earth, A Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese Calligraphers, and Profiles of Chinese Artists either carry special articles on Chu Yun, or have entries about him. His publications include A Collection of the Works of Chu Yun and Wo Xinghua, The Nineteen Ancient Poems Penned by Chu Yun in the Script Style, and A Dictionary of Six Calligraphic Styles.

4:30pm

University Library Gallery

University Library Gallery