Writing the text for the project Tales from a 1493 World Map: Playing with Augmented Reality (AR) was meant to be a straightforward task - just a bit of history, a touch of mythology, and voilà, a finished story. In reality, it turned into a full-scale expedition through time, culture, and a bestiary of fantastical creatures that make Godzilla seem downright tame. Though my journalism background prepared me for chasing deadlines and digging for facts, tackling a 1493 German medieval map brimming with monsters borrowed from Greek, Roman, and other mythologies was an entirely different challenge. Let’s just say neither history nor myth was accompanied by a user guide. For an entire month, Tory, the Head of the library’s Research & Learning Support, and I became part-time historians and mythical creature specialists. We scoured the HKUST library as if it were a treasure trove, navigating dusty tomes and digital archives from museums across Europe and North America. We encountered ancient manuscripts, encyclopedias, and artistic interpretations that looked like the creative output of medieval monks during a very long sermon. The greatest challenge? Distinguishing fact from fiction - or, as I came to call it, playing medieval myth-whack-a-mole. One source portrayed a beast as a noble fire-breather; another insisted it was merely an irritable lizard with attitude problems.

You might have heard the Italian name Ricci – perhaps Ricci Hall, one of the oldest residential halls at HKU. But do you know who Matteo Ricci was? The man who made this Italian name famous in China. Who was Matteo Ricci? Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) was one of the first Jesuit missionaries who tried to spread Christianity in China. He was born in Macerata, a small town in central Italy with a population of just under thirteen thousand. At the age of 20, Ricci was admitted to the Roman College, a Jesuit university renowned for its expertise in natural philosophy. Hmm, what exactly was natural philosophy? Mathematics, astronomy, music, geography, and more technical disciplines like mechanics and architecture. For example, how to craft a globe?

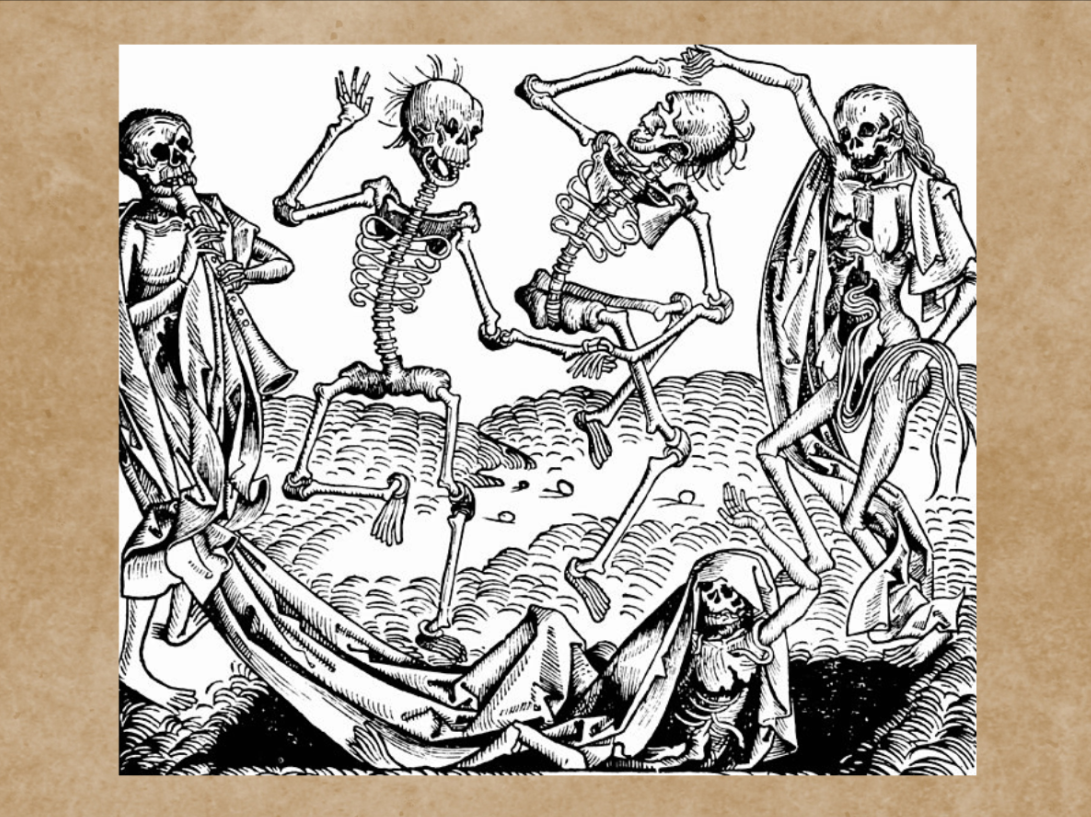

Part 1 discussed how students can fight monsters of anxiety about grades & GPA by laughing and learning with the Wisdom Stone Game. But, some carry around other fears. Since childhood, we’ve become familiar with the idea or cliché of corpses and skeletons coming to life. Others may fear living creatures like spiders or snakes. We get “spooked out” by such things, except when they are silly or pretty. There’s a long tradition of dealing with these fears by confronting or even celebrating them. Here’s an example: Danse Macabre, composed by Camille Saint-Saëns, performed by Lydia Ayers, Andrew Horner, and Stella So. Danse Macabre, also called the Dance of Death, is an allegorical concept said to encapsulate the unconscious fear of death.1 The popularity of the Danse Macabre art such as poetry, music and drama, can be traced back to the 13th century, when Europeans became obsessed with death inspired by the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War.2 This video of a puppet show, available on DataSpace@HKUST, is part of a collection of the music, and puppet productions of the late Dr. Lydia Ayers, a former professor at HKUST, given by her widower, Dr. Andrew Horner, a professor of Computer Science here.