As a staff member at the HKUST Library and a devoted fan of>The Three-Body Problem since my student days, I never imagined that one day I would meet Liu Cixin (劉慈欣) in person, and right here at my workplace. From Ancient Maps to Galactic Orbits.On October 18, HKUST held its Congregation 2025, awarding an honorary doctorate to Mr. Liu Cixin, the first Asian writer to win the prestigious Hugo Award. The same afternoon, Dr. Liu came to our library for a talk. I had the privilege of accompanying him together with a few of my colleagues as he explored our exhibitions, rooftop garden, and special collections. He showed genuine curiosity and appreciation, particularly towards our displays of ancient Chinese maps.A Dialogue on Technology, Human Civilization, and the Future. The highlight of the library visit was of course the talk, held in dialogue-format and moderated byProfessor Liu Jianmei. The venue was packed. As an “insider”, I firsthand knew how overwhelming the demand was: Over 700 registered for just over a hundred available seats. It was harder to get than concert tickets The discussion covered a broad range of topics from how AI is shaking up creative writing, to the future of virtual worlds, and to the sociological implications of the Dark Forest theory.When asked about AI’s growing ability to write fiction, Dr. Liu candidly admitted that even he had experienced a decline in creative passion. AI-generated texts now often surpass human writing in fluency and style, making it difficult to evaluate student work or feel unique as a writer. Yet he also pointed out that human cognition itself is data-driven, much like large language models. As a science fiction author, Dr. Liu remains calmly optimistic. He doesn’t see AI as a threat, but as a potential guide for humanity’s future. “If one day we can’t leave the solar system, but artificial intelligence can,” he said, “then perhaps it can carry our dreams into the stars.” One of the final questions of the talk came from an audience member who asked how Dr. Liu comes up with such vast and original ideas. I was particularly interested in this question myself. His answer was refreshingly honest: most people assume that sci-fi writers effortlessly generate ideas like “laying eggs,” but in truth, it is extremely difficult. Even with intense effort, he said, it can take more than a decade for a good idea to surface. As both a reader and a librarian, I was deeply moved. It reminded me that true creativity isn’t the product of calculation, but of vulnerability of being shaken by the unknown and daring to imagine beyond it. As a Three-Body fan, I was most eager to hear his thoughts on the Dark Forest theory. Dr. Liu clarified that it’s not a metaphor for human society, but an extreme hypothetical model for cosmic sociology. When civilizations are separated by light-years and unable to communicate, “shoot first to survive” becomes a plausible strategy. He emphasized that humans, unlike alien civilizations in such scenarios, can communicate and cooperate. Applying the Dark Forest model directly to humankind is a misinterpretation.

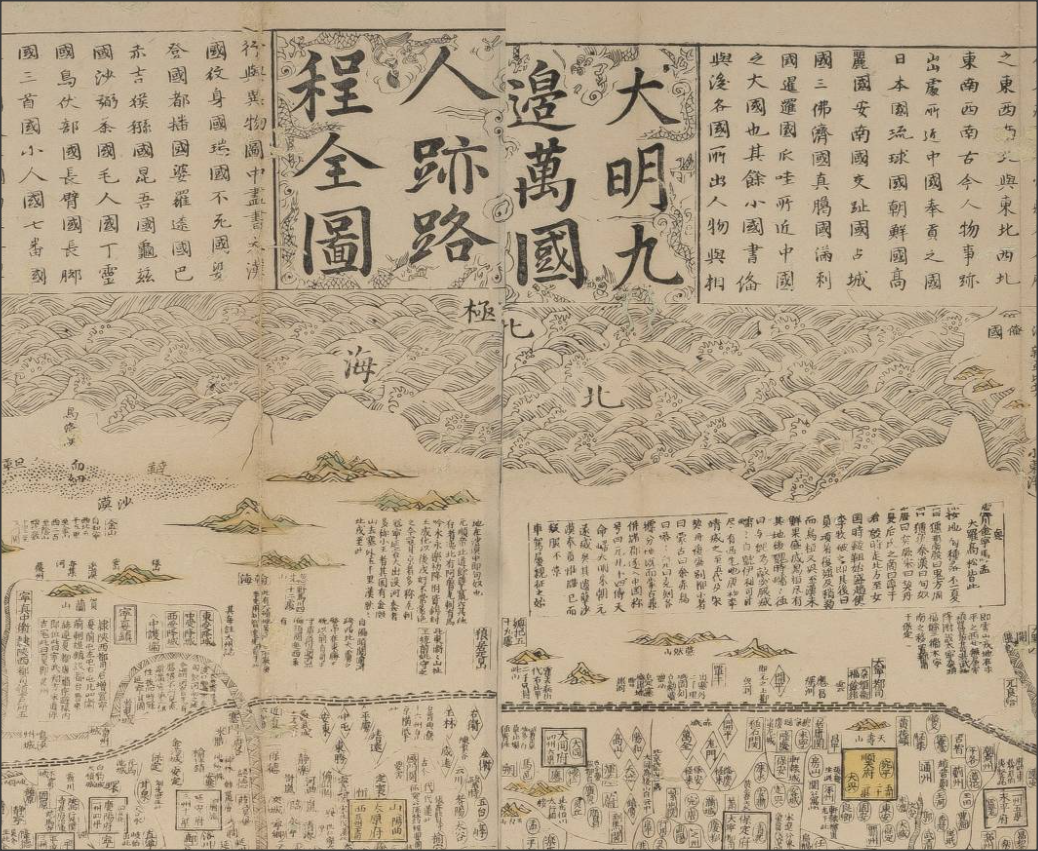

Old maps are visually beautiful; and they carry a lot of interesting stories. The Library hosted a 3-day research symposium last December with map historians from local and overseas institutions. One really memorable talk in the symposium was about this famous Chinese map dated 1644, the year the Ming Empire collapsed: <天下九邊分野人跡路程全圖> (A comprehensive map of the kingdom of China and neighbouring countries). The speaker, Professor Mario Cams of KU Leuven (Belgium), explained that this fascinating map was a hybrid of Chinese and European mapmaking; he told the interesting threads of history in a century of east-west exchanges that led to this map. We do not have a copy of this rare map, but you can find a similar one printed in the 18th Century in our Special Collections. You can examine the image of the 1644 map at this site: look for the latitude scale, north and south poles, Europe, North and South Americas (separated); these are the typographical knowledge from the West, and are scattered around the edges of the map. However, the bulk of the map in the middle is the Ming Empire administration, which is not intended to represent geographical reality. To weave the story of the map, Professor Cams started in 1555, the era when 2 Chinese maps from Fujian travelled to Europe via merchants in Southeast Asia. Afterwards, Jesuit missionaries brought European geographic knowledge to the East, forming the basis of this "hybrid map". An important thread in the story is the Ming book publishing culture.