Introduction

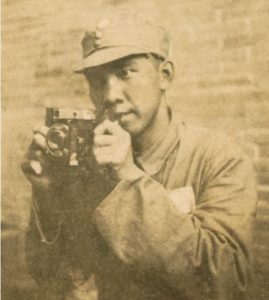

One of the most influential Chinese photographers of his generation, Sha Fei captured some of the most iconic images of wartime China from the late 1930s to the 1940s. His work reflects his deep humanism and his belief in the power of photography to awaken the people. Following his tragic execution in 1950, Sha Fei’s name was erased from history, only to be rediscovered in the 1980s.

One of the most influential Chinese photographers of his generation, Sha Fei captured some of the most iconic images of wartime China from the late 1930s to the 1940s. His work reflects his deep humanism and his belief in the power of photography to awaken the people. Following his tragic execution in 1950, Sha Fei’s name was erased from history, only to be rediscovered in the 1980s.

Thanks to his daughter Wang Yan’s generous donation, photographs in this exhibition illustrate Sha Fei’s extraordinary journey from a photo enthusiast in Shantou, Guangdong, to a Leftist photo-journalist in Shanghai, and finally to a war photographer and editor on the Jin-Cha-Ji war front in North China.

Sha Fei was born Situ Chuan in Guangzhou on May 5, 1912, several months after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty. After graduating from a radio school in 1926, he volunteered for the National Revolutionary Army and participated in the Northern Expedition as a wireless operator. While working at the Shantou Radio Station between 1931 and 1936, he was influenced by Western pictorial magazines and became intensely interested in photography. His early images, while aesthetically modernist, were imbued with deep sympathy for working people and the weak in society.

Sha Fei joined the Shanghai-based “Black and White Photographic Society” in 1935 and studied Western painting at the Shanghai Art Academy in 1936. In October of that year, he captured the final images of Lu Xun (11 days before Lu’s death) and rose to fame as a leading photo-journalist.

After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, Sha Fei went to the Shanxi frontlines in September to report on Chinese resistance. Buoyed by the Eighth Route Army’s victory at Pingxingguan, he joined the Communist-led force in December. In the ensuing months, he produced dozens of images of Chinese troops in action atop the ancient Great Wall—powerful symbols of national resistance. In 1942, in a Hebei valley without electricity, Sha Fei and his comrades founded the Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial, the first Chinese-English magazine in Communist areas. He also trained a corps of photographers. During a Japanese attack in 1943, Sha Fei was wounded and nine others were killed trying to protect film negatives.

In the eight-year War of Resistance, Sha Fei took more than a thousand photos. These evocative images, rendered with emotional intensity and artistic rigor, documented enemy brutality, combat scenes, military training, mass mobilization, political participation, and the Nationalist-Communist United Front. He also recorded the activities of various foreigners in Communist base areas, including American military observers and rescued pilots; a British radio specialist; Canadian doctor Norman Bethune; Indian doctors; Korean nationalists; as well as Japanese prisoners of war. Some of his last works captured U.S. General George C. Marshall’s mediation effort to prevent the Civil War in early 1946.

Nearly all of Sha Fei’s photographs focus on people—mostly common people, including women and children—whose pain, fortitude, optimism, and dignity come alive through his lens. Remaining unfettered by Soviet rigidity or Maoist conformity, his images exude sympathy and spontaneity, striking a nuanced balance between artistry, authenticity, and propaganda.

Sha Fei belatedly joined the Party in 1942 and was repeatedly criticized for being “more like a democrat” than a Communist. Years of overwork, battle wounds, and political campaigns took their toll on his health. In May 1948, he was admitted to the hospital for tuberculosis and was never cured. Apparently suffering from mental illness, Sha Fei shot and killed his Japanese doctor in December 1949. A military court sentenced him to death. He was executed on March 4, 1950, five months after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Buried with him was a small metal box containing the negatives of Lu Xun.

“Although Sha Fei’s life stop-framed at age 38,” the late historian Gao Hua has suggested, “his death allowed him to eternally retain his authenticity.” As he had aspired when renaming himself, Sha Fei had “become a grain of sand forever flying free in the sky above his homeland.”

David Cheng CHANG, Assistant Professor of the Division of Humanities

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology