前言

有人說三十年代是先秦以後中國又一個諸子百家的時期,英才輩出,奇峰相迭,湊巧的是,三十年代也是中國水彩畫的第一個高峰期。

水彩畫十五世紀始於歐洲,十八世紀在英國成為獨立的畫種,在西方至今仍很風行。中國三十年代留學歐日的藝術家,油畫之外,大都擅長水彩,其間林風眠、龐熏琴、劉錦堂諸人是諳熟此道的大家。林風眠瀟灑淋灕,龐熏琴精深細密,劉錦堂逸筆草草。我尤其喜歡劉錦堂,寥寥數筆,活畫出江南的明媚清秀,十分的中國化。三十年代的中國,民族意氣高昂激越,民族化是一般有血性的中國藝術家苛意而自覺的追求,又由於三十年代的畫家多半學養深厚,因而其追求有底蘊,不盲目,高遠宏闊,創作了於今日依然有啟示性的範例。

五十年代是中國水彩畫的又一個高峰期,俗稱洋涇浜的上海是中心,樊明體、林曦明、沈柔堅、張充仁、李劍晨等都曾風風光光過一段時光。然而,水彩畫似乎天性傾向抒情,亦如音樂中的慢板,絕少凝重的氣象,無力承載那時代沉甸甸的政治,自然漸漸消沉了。

八十年代是第三個高峰期,改革、開放,人的主體意識始獲覺醒,人為的價值誤區逐漸消解,人們可以憑借才能與興趣選擇志向。水彩畫再次被人們垂青,而對光明的向往與對生活多樣化的追求則把水彩畫推向新世紀。這一時期水彩畫家人數最多,展覽頻繁,建立了全國性的水彩畫家協會,如果說這一時期是中國水彩畫空前繁榮的時期,似不為過,而本質地代表這一時期中國水彩畫的特徵是風格指向的多樣性,人們不再有新顧慮,敢為人先,爭為人先,顯示出這一時期人們心靈的自由與蓬勃。至於這一時期的遺憾則是尚未出現足以代表一個時代的大家。

蔣智南介入這一領域是從九十年代開始的,一九九一年首次作品《海》參加北京市水彩畫展獲好評;一九九二年其作品《康陵石碑》即應邀赴台灣參加首屆大陸水彩名家邀請展,從此,作為這一時期中國水彩畫領域的重要作者,屢屢參展,開始建立他在中國水彩畫領域的學術地位。

蔣智南畢業於中央工藝美術學院染織美術專業,染織設計在沒有計算機之前,全賴手繪,其材料是水粉或水彩,這對他日後能夠輕鬆地駕馭水彩無疑是個鋪墊。

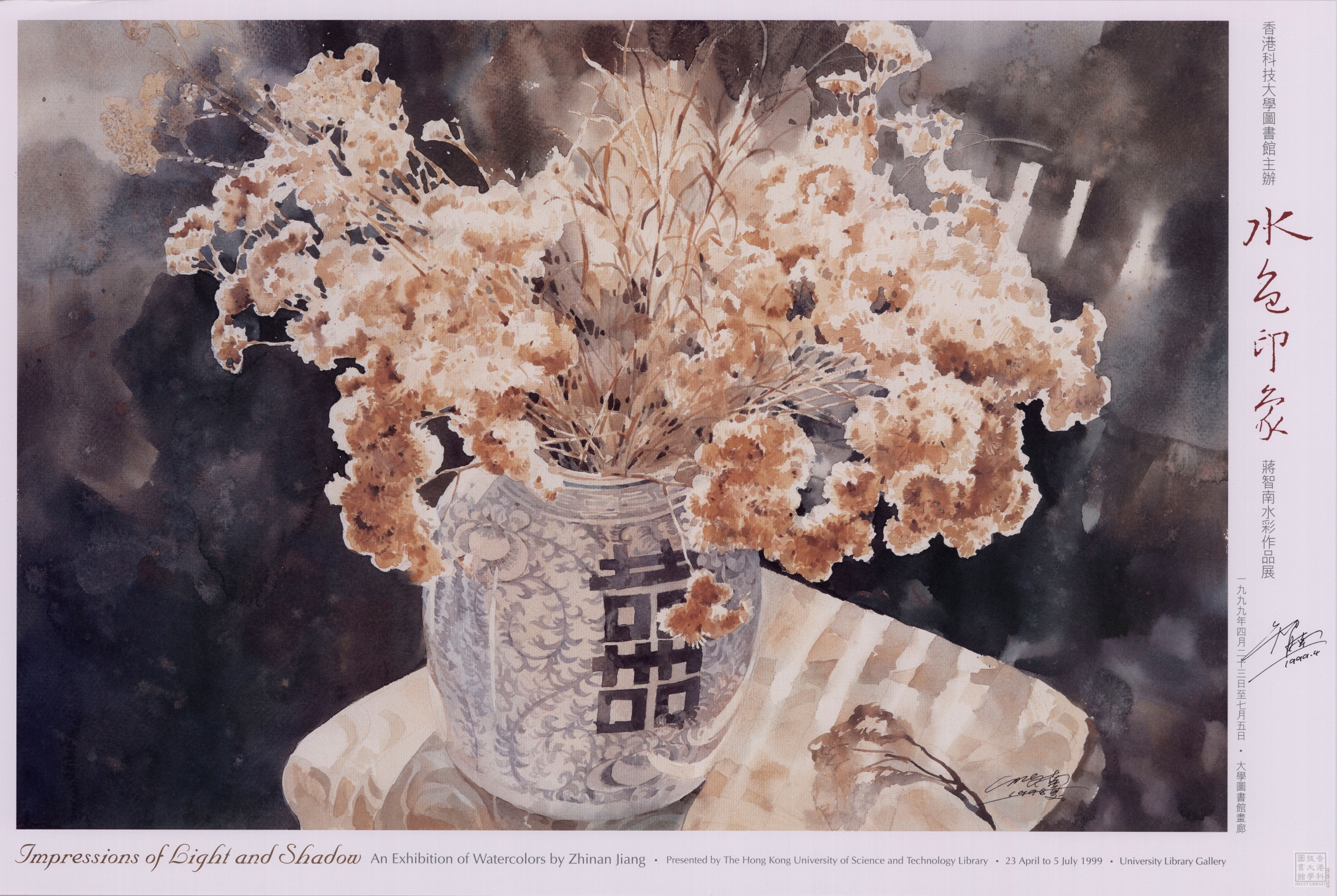

蔣智南的水彩畫依我看大致可分三個階段,第一個階段以寫生為主,其對象似有選擇,亦喜選擇田壟、山岩、花卉、村落、家與家中的藤椅、他愛人及與他愛人朝夕廝守的貓,看似不經心,但確有親疏,都是陽光下關聯著他情感世界的人與物。這一階段有兩個特徵,一是對光的崇尚,暖暖的棕色調,充滿了真誠地擁抱生活的溫馨;二是筆法細膩,以物體的自然肌理作為建立畫面視覺秩序的媒介,具象中暗示著某種抽象,而後一種似乎是真正支撐畫面結構邏輯的骨架。

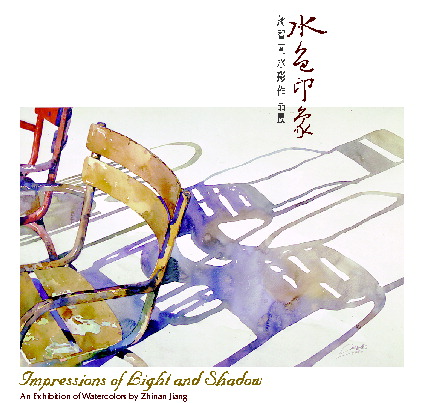

第二階段是《自行車系列》,依然是躍動與閃爍的光,實物與投影互為主次,相互映襯,說不清究竟那一個是畫面的主體,其實所謂自行車不過是一種憑藉而已,畫面秩序明顯地抽象化了,先前似乎還吞吞吐吐潛藏於畫面深層的邏輯終於浮顯於表面。從模擬一種具體的物象,到內心秩序的陳述對蔣智南是一次突破,而偏重塑造的筆法逐亦變得淋灕酣暢,活潑而遒勁,更加吻合了水彩的秉性。

第三階段是他在巴黎國際藝術城進修期間所畫的歐洲所見,因為要留下一段記憶,因而不能迴避當時的真實情景,雖如此,畫面中景物的取捨,構圖,色調還是多了一分理性,客觀中滲透著他對他意欲記錄的事物的心靈軌跡,精神的一面成為他期待表述的第一需要。與第一階段顯然不同了,技巧上亦更加嫻熟而洗煉,手與心相合,景與情相融,沉而老辣,他已是一個很成熟的水彩畫家。

光在蔣智南的水彩畫中具有十分重要的意義,我甚至以為光對於蔣智南不僅是一種媒介,而是一種目的。我很信服他對光的敏感,亦為其把光處理得那麼生動,那麼空靈感到驚訝,光對於生命不僅是一種需要,也是一種信仰,我不懷疑蔣智南也是這樣想的。

蔣智南是把水彩畫當作終生的事業對待的,這並不容易,今天的中國似乎只有中國畫和油畫才是藝術的主體,在主體之外尋找安身立命的去所,需要勇氣,也需要自信,我相信他會有更多的成功。

世界無論多麼依賴國際接軌,藝術中的民族悟性,包括民族形式和民族情感,在可以預見的將來依然很現實,作為舶來品的水彩畫不會是例外,三十年代一批傑出藝術家的傑出努力我依然以為足資借鑒。

杜大愷

一九九八年 北京

| 1963 | 生於中國河北承德 |

| 1981 | 畢業於河北工藝美術學校 |

| 1988 | 畢業於中央工藝美術學院並留校任教至今 |

| 1991 | 作品《海》參加北京市水彩畫展 |

| 1992 | 作品《康陵石碑》參加台灣首屆大陸水彩名家邀請展 |

| 1993 | 作品《白洋澱》參加 “香港北京水彩學會93年展” 參加 “五人畫展” |

| 1994 | 在深圳博雅畫廊舉辦 “蔣智南水彩畫展” 作品《早春》參加韓國舉辦的 “中國水彩畫精選百人展” 作品《太行人家》參加 “中國當代水彩畫展” 作品《過去的故事》參加 “現代水彩畫邀請展” 作品《無題》獲 “三峽書畫大賽” 特等獎 作品《岩石》參加中央美院、中央工藝美院、日本東京藝術大學聯展 |

| 1995 | 作品《星期日》獲 “中國首屆青年水彩畫大展” 學術獎 |

| 1996 | 作品《光與影的對話》獲 “全國第三屆水彩、水粉畫展” 銀獎 在北京雪白畫廊舉辦 “蔣智南水彩畫展”設計並中選 “中國‧新加坡聯合發行城市風光特種郵票” 作品《藤椅》參加全國首屆水彩藝術展赴法國巴黎國際藝術城進修學習,並在巴黎國際藝術城舉辦畫展在法國楓丹白露舉辦畫展 |

| 1997 | 作品《影子裡的咪咪》參加中韓水彩畫聯展 作品《陽光燦爛的日子》參加中國藝術大展 舉辦 “歐洲之旅—蔣智南水彩畫展” 應邀擔任 “全國青年水彩畫展” 評委 作品入選《中國美術全集‧水彩卷》 |

| 1998 | 作品《妻與貓》參加全國第二屆水彩藝術展 赴美國三藩市和西瑞寇斯兩地舉辦畫展 參加深圳美術館舉辦 “中國青年水彩畫家邀請展” |

| 1999 | 在香港科技大學圖書館畫廊舉辦 “水色印象—蔣智南水彩作品展” |

下午4時30分

香港科技大學圖書館畫廊

Opening Remarks

I feel greatly honored to have been asked to introduce our artist this evening. I also feel a bit embarrassed to speak at an art exhibition. Being a linguist who deals primarily with sounds and graphs, I know very little about art. I must admit, however, that I love art and I adore beauty. I came down to the library three nights ago for a sneak preview of today’s exhibit, and for reasons I cannot explain there was something in the paintings that I connected with right away. An instant click, an attraction at first sight. I got hold of a catalogue, which I took home, where I spent an hour or so studying the illustrations and the introduction by Du Dakai. I felt all the more attracted to the pictures; but I was also all the more lost for words to express my feelings. Mr. Jiang, whose acquaintance I have had the pleasure of making this evening, is very talented. He did not become a professional artist until the early 1990s and within ten short years he has gone through many phases and stages of transformation, as outlined in the preface of the catalogue, and now is one of the most celebrated watercolorists in China. According to Mr. Du, Mr. Jiang’s early works are mainly sketches from daily life, concrete objects that transmit a certain sense of abstractness. In his next phase, as represented by the Bicycle series, he moved from imitating the concrete to expressing the logical order of his inner mind. In his 1998 paintings, the third stage in Mr. Jiang’s art, he is more attracted to the spiritual aspect of a scene, and he has achieved an even better mastery of technique, an integration of scenes and feelings. I am not an artist or an art critic, and I can’t say very much about technique, which is of course one of the chief factors that account for an artist’s success. For me, it is the vision, the feelings, or the spiritual inspiration in a work of art that distinguish a great master from a skilled artist.

One of the pictures I like best in today’s exhibition is “Village Child”. A young child, most likely a girl, leans against a stone stand, trying to catch a few moments of rest, perhaps after a day of hard work. Just behind her sits a bundle of sticks, which, mostly likely, she will soon carry upon her shoulders. She stands in a singularly odd position, as you might have noticed, with her body forming a cross, a sign of crucifixion. In fact, we don’t see a happy child in the picture, but a child whose face betrays little expression. She looks out, but at whom? Is she asking for help? Or telling us to leave her alone? We don’t know. But there is, I noticed, a large empty space in the picture. Even though the child is the focus of the painting, she occupies only one-third of the space and half of the picture is a huge blank. Just imagine what the picture would mean to us if the empty space were removed. The picture would look cluttered, especially where the colors are strong and heavy. Once that extra space is added, the world extends and we feel an instant lifting of a burden and tension. That space seems to invite us to join the girl, and yet the expression on her face is not necessarily one of invitation. An anomaly of some sort, a contradiction that captures our fancy and fantasy.

In fact, I feel that Mr. Jiang has successfully used empty space to invite his audience to join him in constructing or telling a story. And not only in his “Village Child”. Compare the Bicycle series with another recent picture, “Untitled”. The bicycle series features bikes in fast motion, almost too fast to be captured with strokes and lines. We see a montage of colors in different lights, an abstract form of vitality and speed. Yet, we never see the rider. We know a person is there to peddle the wheels. Or, have we transformed ourselves into the riders? In his 1999 picture, which also features a bicycle, we are shown only half of the vehicle, the first half hiding behind a wall in a back alley. Again, it is a picture with no human image, but we feel a human presence. We are presented with an empty or deserted alley. Who was there? Who came on a bike? Where is the rider now? Inside the house behind those walls? Again, an intimate story waits to be told.

A picture can tell more than a thousand words, and I think the magical powers of Mr. Jiang’s paintings are particularly effective in invoking our imaginations. He manipulates space to create a space for our participation, using shadows to add to that mystery of presence and absence. For example, in the picture of chairs in the Luxembourg Gardens, not only do we see empty seats, we also find that shadows on the ground are depicted in two-thirds of the picture. These are not reflections of people but rather images of deserted, rustic garden chairs. There are no visitors to the park, and we seem to have the entire space all to ourselves. Painted in a sunny brown color and a cooling blue, it is a very warm picture. Don’t we want to take a seat and enjoy a balmy afternoon in this French garden?

Mr. Jiang’s pictures take us to different parts of the world — a pier in Venice, the Berlin Wall, a back alley in a rural town, a lotus pond where we almost seem to witness the passage of time. He shares his visions with us and he lets us into a world of light and shadow, a world that he creates in watercolor, a world whose infinite images of change he reproduces and captures for our appreciation. And, for your generosity in sharing your talents and stories with us, I thank you on behalf of the audience and the University of Science and Technology.

H. Samuel Cheung

Hong Kong, 1999

開幕辭

我非常感謝周館長的邀請,讓我今天能躬逢盛會來參加這個畫展,同時見到畫家本人蔣智南先生。這兩天我已經來過場地數次,先睹為快,看了展出的作品。這次展覽的題目是“水色印象”。水色這個詞,不知是誰給起的,但是比諸水彩,實在高明許多。水彩的「彩」給人一種五彩繽紛,濃艷絢爛的感覺。而水色則還我本色,水色交融,或濃裝飄忽,或淡抹動人。環觀蔣先生這次展出的四十多幅大小製作,燦爛中又見淡雅,給人一種反樸歸真的感覺。水色本來是最難捉摸的形象。水中之色,飄浮不穩定,眩目而又恍忽。蔣先生的畫正是以影以光來捕取對景、對人、對物的剎那印象。我不是內行人,這種外行話,其實是我這兩天來看畫時心裡的感覺。而最使我心動的是蔣先生在畫中對空間的使用。蔣先生的畫,虛實對比很強烈,虛比實似乎還多,更能添增畫裡的空靈感覺。比方這一幅 “村童” 的畫,用色相當的濃,但因為空白佔了二分之一,濃相對地淡化,就不會使人感到沈重壓迫。試想這一幅畫中把空白去掉,突出了村童,畫面就會顯得擁擠,舒暢和擠迫的對比,也許更能表現出畫中的特點。這個小孩,似乎是個女孩,倚石墩而立,雙腳微微交叉,她背後有一捆竹篦,手不離竹。是小孩兒玩耍後的小憩,還是她工作後暫時放下竹筒,偷空喘息?她站立的姿態雙手很像橫伸一個十字架,這象徵什麼?她臉上顯示的不是微笑或童真。是迷惘?是無奈?是漠然?在她面前卻是一大片空白或空地,她不望向空地,而望向畫外。這又是什麼意思?是在邀請看畫的人進入這個空間?沒有留空,畫就會顯得死實;有了空白,就有了想像的空間。蔣先生有一系列的畫,題作自行車。簡單的筆觸,大膽的蒙太奇手法,捕捉了自行車的奔馳和衝勁,但是畫中並沒有騎車的人。我們只通過畫面而感到騎者的存在,活力溢滿紙面。與此相對是蔣先生1999年的近作「無題」,是後巷裡的一輛自行車 — 應該是半輛,車的前半藏在半堵牆後。這不再是奔馳的自行車,一切歸於靜寂。但是畫中留有許多空白,影子更惹人遐思,是誰來了?人又去了那兒?從小門進去了嗎?每一幅畫都是一個故事,而這個故事的發展卻是我們看的人自己添補進去的。畫者一兩筆的勾勒,卻勾引起我們無限的幻想。意在畫外,這是上等的好畫。這次我有機會在這兒看到這許多畫,想了很多故事,又見到了畫者本人,實在感到十分興奮。可惜我不是一個小說家,更不是一個畫家,所以只能野狐禪地說一下自己的感受。不過我也想借這機會代表科大向蔣智南先生再次致謝。

張洪年

一九九九年四月廿二日

香港科技大學圖書館畫廊