This week, we present a study on how HKUST researchers write the "Data Availability Statement" section in their papers. Clueless about DAS or not sure how to share your research data? Read our analysis here.

In recent years, an increasing number of publishers have implemented policies mandating researchers to share the data supporting their findings and publications. Notably, publishers like Nature and BMJ have made such data availability statement (DAS) disclosures a prerequisite for manuscript submission across all their journals, while others, like Wiley, actively encourage the inclusion of data availability statements in manuscripts.

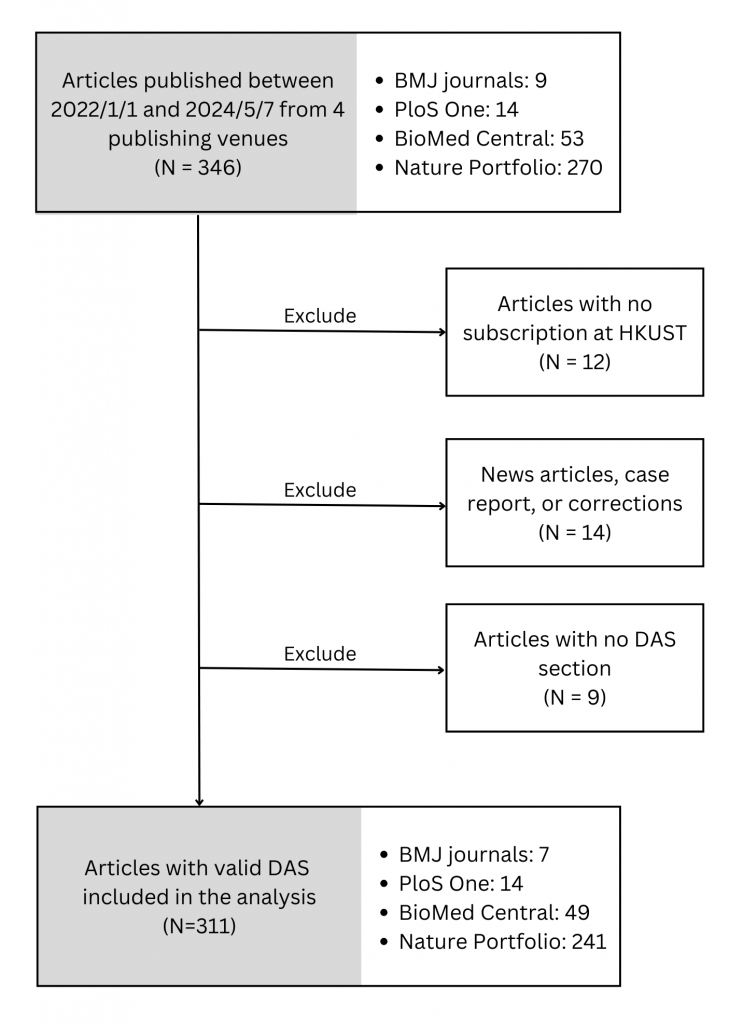

Interested to explore how HKUST authors are sharing their research data in journal articles, we analyzed data availability statements in journal articles published by BioMed Central, BMJ, Nature Portfolio, and the PLoS One journal. These papers were retrieved from OpenAlex on 7 May 2024 with the publication date set between 2022 and 2024. Following the exclusion criteria outlined in Figure 1, we identified and included 311 articles with a DAS in our analysis.

Figure 1. DAS Inclusion Flowchart

Data Availability Statement Coding

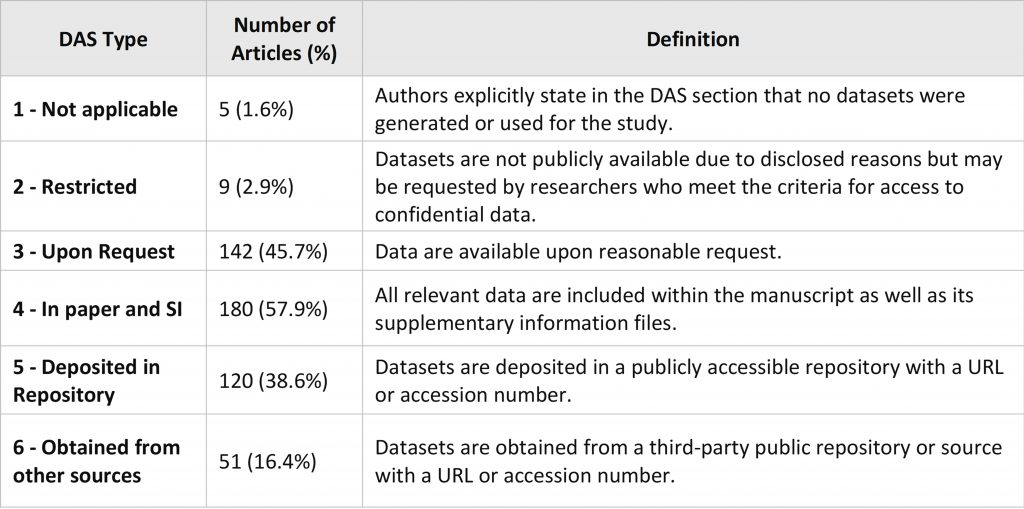

Data Availability Statements of each paper were coded with 6 types (Table 1). The "Number of Articles" column represents the count of papers that adopted each particular data sharing method, while the "%" indicates the proportion of articles that used that method out of the total 311 articles.

It is important to note that in some cases, authors employed mixed data sharing methods in a single paper. As a result, the total percentage across all types exceeds 100%, as articles could be coded into more than one type.

Table 1. Definition of the Coding Types of the DAS.

Single or Mixed Methods for Data Sharing

One Method

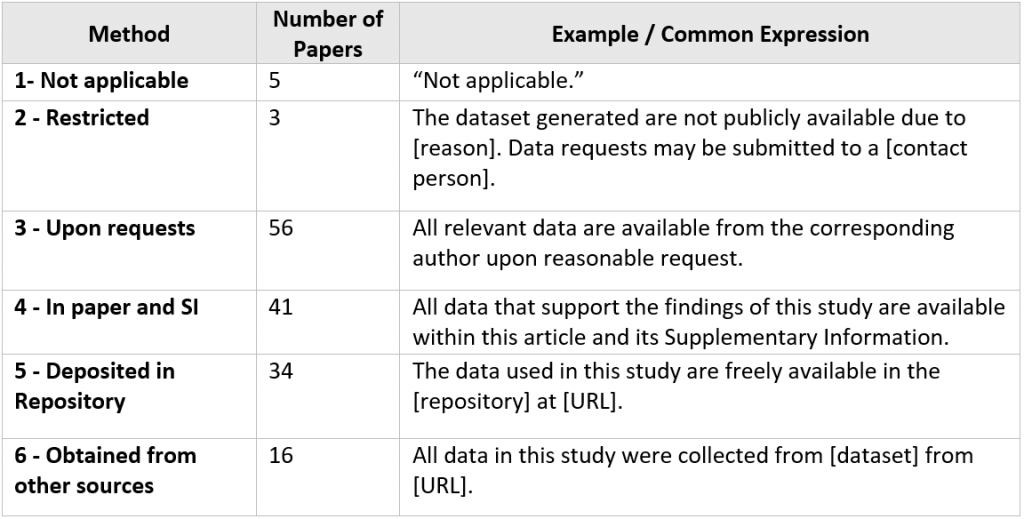

A total of 155 papers (49.8%) used a single method for data sharing. The distribution is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Articles with One Data Sharing Method

- Types 3 and 4 (“Upon requests” and “In paper and SI”) are the most frequently used data sharing method.

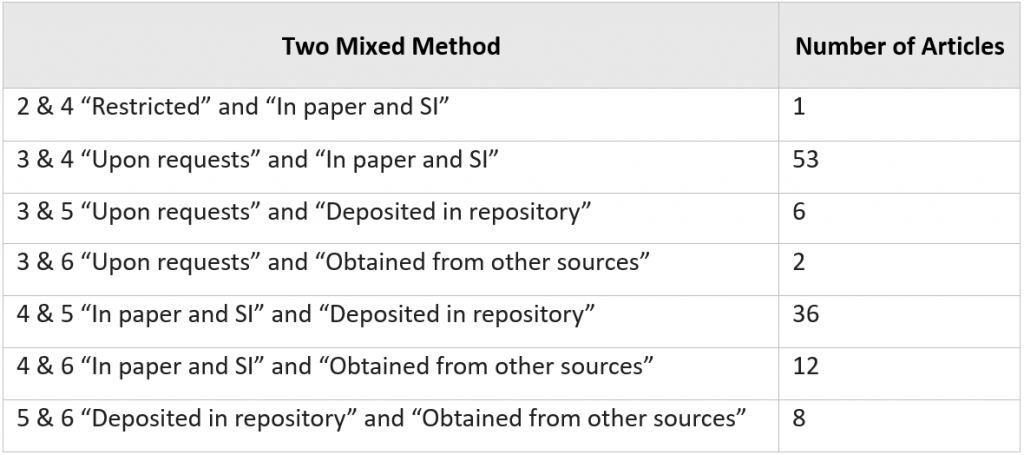

Two Methods

A total of 118 papers (37.9%) employed two methods for data sharing, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Papers with two data sharing methods

- The combination of Types 3 and 4 (“Upon requests” and “In paper and SI”) is the most frequent, comprising 44.9% of the two-method papers.

- The combination of Types 4 and 5 (“In paper and SI” and “Deposited in repository”) is also significant, representing 30.5% of the papers.

- Type 4 appears in 86.4% of the two-method combinations.

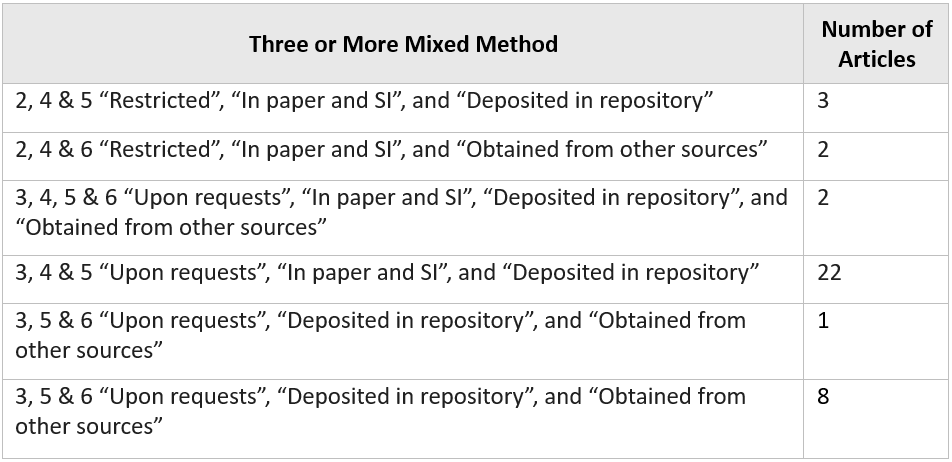

Three or More Methods

A total of 38 papers (12.2%) used three or more data sharing methods, with specific combinations detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Papers with Three or More Data Sharing Methods

- The combination of Types 3, 4, and 5 (“Upon requests”, “In paper and SI”, and “Deposited in repository”) is the most common, accounting for 57.9% of the papers with three or more methods.

- Type 4 is again prominent, appearing in all but one combination.

Findings:

- Dominance of "In Paper and SI": Type 4 is the most frequently used method across all categories, indicating that researchers still rely heavily on sharing data within in the publications themselves.

- Combination Trends: The most common combinations involve Type 4 (“In paper and SI”) paired with either Method 3 (“Upon requests”) or Type 5 (“Deposited in repository”). This suggests that researchers are inclined to provide data both directly in their publications and through additional means.

- Single vs. Multi-Method: While a significant portion of papers (49.8%) rely on a single method, a notable 50.2% employ two or more methods, indicating a trend towards more robust data sharing practices in recent research.

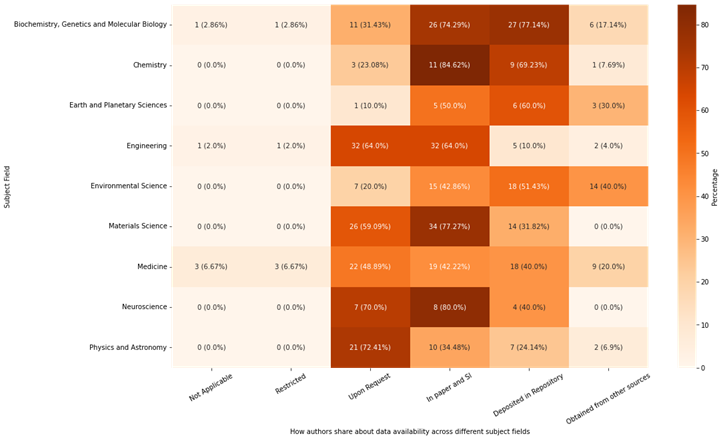

Data Sharing Across Subject Fields

OpenAlex assigns topics following a “domain-field-subfield-topic” system to work indexed in the database. In this study, we extracted the “field” for each paper and explored if there is any pattern of data sharing practice across different research fields. The heat map (Figure 2) presents an analysis of data sharing practices across various research fields, focusing on subject fields with at least 10 articles to ensure representativeness. The count of articles and percentage within each field are indicated in each cell.

Figure 2. Data Sharing Practices Across Various Research Fields

Findings:

- Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology, Chemistry, Earth and Planetary Sciences, and Environmental Science show strong open data sharing practices, particularly through repository deposition.

- Physics and Astronomy, Neuroscience, Materials Science, and Engineering are more conservative, with a lower reliance on repositories and external data sources.

- Medicine reflects a balanced approach, leveraging both repositories and In Paper and SI for data sharing.

- Environmental Science, Earth and Planetary Science, Medicine, and Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology mentioned more use of external data sources due to their subject nature, which often involves large scale, long-term and collaborative data collection efforts.

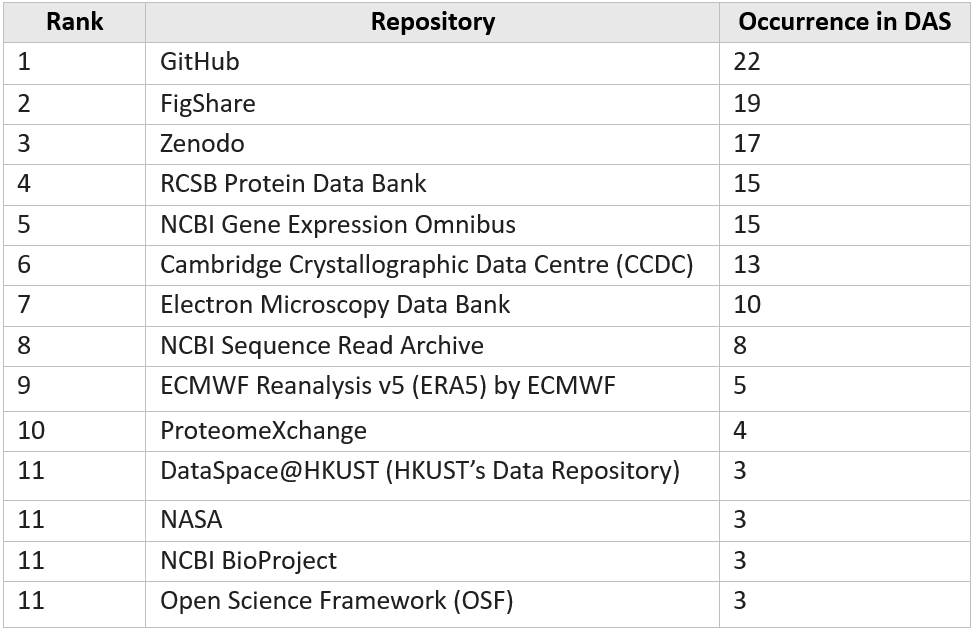

Frequently Mentioned Repositories and Sources

The analysis found 151 articles, which is about a half of the papers in the study, mentioned that their data have been deposited in a data repository or obtained from an external source (Types 5 and 6). Table 5 shows the data repositories that were mentioned in at least three of the articles. We are pleased to see HKUST’s Data Repository has been reported by three papers (#1, #2, #3).

Table 5. Repositories with at least 3 mentions

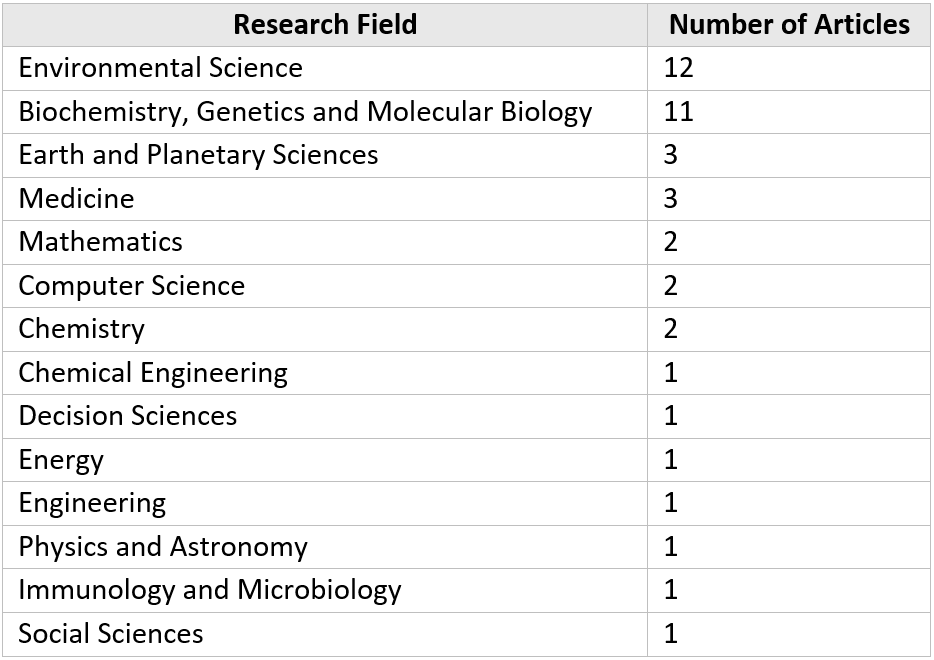

The analysis also revealed that 42 articles mentioned three or more data repositories in their work. Table 6 provides a breakdown of the fields by these articles, and it suggests that the use of multiple data repositories was particularly prevalent in Environmental Science and Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology research. In some papers (#1, #2), researchers even mention as much as nine data sources for their study.

Table 6. Breakdown of articles with at least 3 data sources by research field

“Sharing” Restricted Data

In our data management workshops, we've often encountered researchers expressing reluctance to share their data, as it may be confidential or part of an ongoing research project. In such cases, we often explain that sharing the availability of data does not necessarily equate to making all data openly accessible. In a DAS, simply acknowledging the availability of confidential data can satisfy the requirements of the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data sharing principles.

In our study, we identified 9 articles that described the availability of restricted data. These examples provide good insights into the common reasons for data access limitations and how researchers can effectively communicate these in their DAS.

Ethical/Privacy Concerns

This is the most frequently cited reason, particularly when dealing with patient data or genetic information. Typical wording includes “restrictions of hospital regulations and patient privacy (source),” “data privacy laws related to patient consent (source),” or “ethical restrictions (source).” In these cases, data access may require approval from a review committee or data management group, and de-identified data might be shared after the necessary approvals are obtained.

Informed Consent

Data collected before a certain date may not have the proper informed consent for public release. The wording used includes “Per NIH policy, samples obtained after January 2015 cannot be uploaded to dbGAP without specific patient consent (source).” Accessing such data may involve contacting the corresponding author or following specific procedures outlined.

Commercial Restrictions

Data may be licensed from commercial entities, and the wording used reflects this, such as “commercial restrictions apply (source),” “license of the datasets used (source),” or “patent filing (source).” In these instances, the data is not publicly available, and accessing it may require contacting the third-party data provider or the corresponding author.

Final Remarks

This exploratory analysis has provided insights into the data sharing practices of HKUST researchers. The key findings underscore the continued dominance of the traditional method of sharing data within the paper and supplementary information (Type 4), alongside a growing trend towards the adoption of mixed data sharing approaches.

The analysis also revealed disciplinary differences, with some research fields, such as Biochemistry and Biology, Chemistry, Earth Sciences, and Environmental Science, demonstrating stronger open data sharing practices through repository deposition. Lastly, we identified several frequently mentioned repositories for data deposition such as GitHub, FigShare, Zenodo, RCSB Protein Data Bank, and NCBI databases.

Limitations

When interpreting the results and drawing conclusions from this study, it's important to consider its limitations and scope. Firstly, the analysis was constrained to articles published in three publishers (Nature, BMC, BMJ) and the PLoS One journal, chosen based on their mandate for the inclusion of a Data Availability Statement. In future research, the scope could be expanded to include journals or publishers that encourage or promote the use of DAS, allowing for an evaluation of compliance rates across a broader spectrum of editorial policies.

Some publishers, such as Springer, clarify that DAS do not necessarily mandate data sharing, but rather aim to increase transparency around data availability. Our analysis has identified instances where DAS, although present, does not denote the accessibility or public availability of research data. For instance, data accessibility may be available upon “reasonable request,” indicating a potential inconsistency between the inclusion of DAS and actualized data sharing practices. Expanding the analysis to a more diverse set of journals and investigating the relationship between DAS statements and actual data sharing behaviours could yield a more holistic understanding of data transparency and accessibility in the scholarly communication landscape.